Microfinance is big business. Since Mohammed Yunus and Grameen Bank won the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize for bringing economic and social development to poor communities via micro-loans, the movement has flourished worldwide. Today, more than 10,000 microfinance institutions provide around $40 billion to more than 70 million borrowers. Yet about 40 percent of that activity is in India, and though Grameen America has helped more than 100,000 borrowers since it was founded in 2008, the microfinance model hasn’t fully taken off in the US. Steve Wanta plans to change that.

Wanta is the co-founder and CEO of JUST Community, an Austin-based nonprofit that provides investments to low-income female entrepreneurs — starting with Hispanic women — to help them lead better, more financially secure lives and create more resilient communities. After a decade working in the microfinance sector via Whole Foods Market’s Whole Planet Foundation, Wanta was tasked with awarding $1 million in lending capital to a US-based organization that could serve entrepreneurs needing loans less than $5,000. He couldn’t find a viable option. “What I came to realize,” he says, “is that in the US, there are very few organizations offering sufficient, affordable opportunities to entrepreneurs without requiring credit scores or elaborate business plans; there’s not the sort of approach that is so common around the world.”

But don’t think that this common approach hasn’t spread here because the US doesn’t have a need for it. On the contrary, the US has its own financial inclusion problems. Nearly 27 percent of US households — 90 million people — are unbanked or underbanked. Sixty-three percent of Americans don’t have enough savings to cover a $500 emergency. Many small-business owners and entrepreneurs lack access to capital. Only 4 percent of small business loans from mainstream institutions go to women. Meanwhile, Latinos and African-Americans tend to launch businesses starting with only a third as much capital as their White counterparts.

Just co-founder Steve Wanta(right) with Maria Gonzalez, one of JUST’s first clients.

Yet, as Wanta points out, between 1990 and 2012 the number of Hispanic immigrant entrepreneurs more than quadrupled, going from 321,000 to 1.4 million. “These numbers show that there is a natural entrepreneurial spirit among Hispanic women,” he explains, “even as they remain excluded from the financial markets, leaving a large pool of untapped talent.”

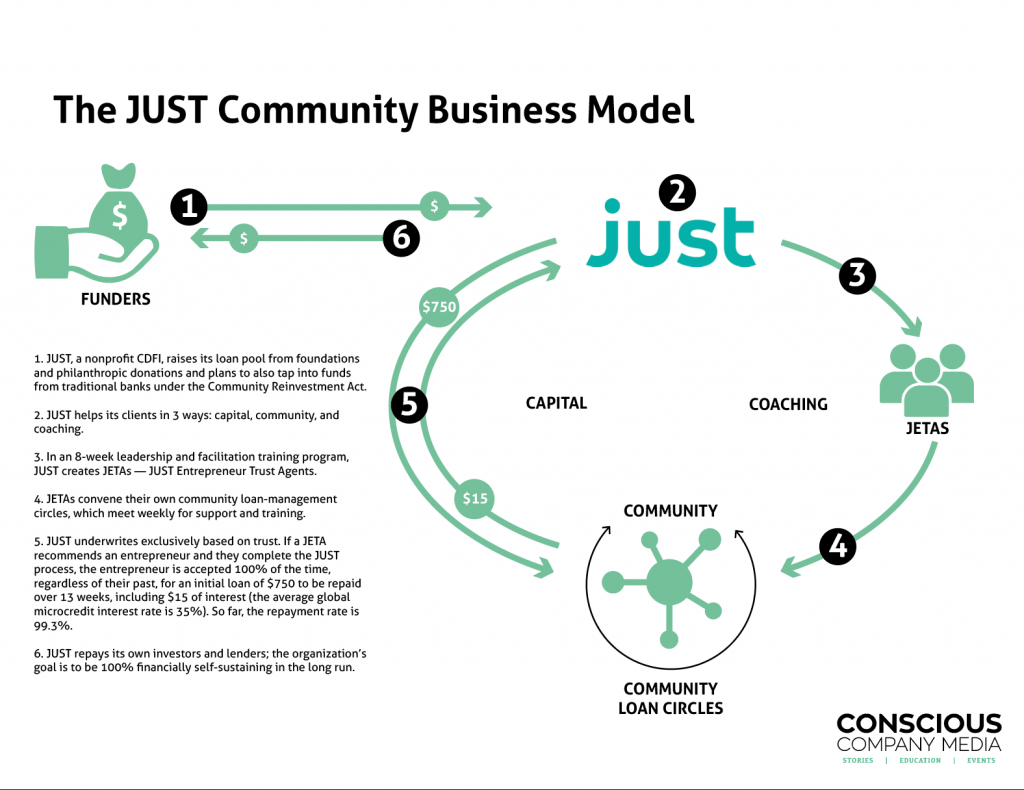

Since 2016, Wanta and the JUST team have been iterating a microfinance model to help unleash that talent pool. They use a three-pronged approach offering a combination of capital, coaching, and community to help their clients achieve JUST’s higher purpose: a life with more joy and less stress. “We’re trying to prove we can put those three things together to uniquely serve low-income entrepreneurs at large scale,” Wanta says.

JUST’s key innovation on microfinancing is leveraging loan recipients to scale the program. After eight weeks of leadership training, loan alums, called JETAs — JUST Entrepreneur Trust Agents — form their own lending circles and invite women they trust to join the loan program. “As long as our JETAs trust these entrepreneurs, we trust them, and we lend them $750,” Wanta says. JETAs then facilitate weekly group meetings that offer coaching on building stronger businesses, taking control of money, building better money habits, and increasing social capital. “The community helps keep the entrepreneurs on track in reaching their financial and business goals,” Wanta says. “And when JETAs manage their own lending circles, they enable JUST to implement a high-touch program at a low cost.”

In 2018, JUST plans to expand its business to another market (Dallas), bring its JETA training program online, and take advantage of its new status as a certified Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) to expand its loan capacity. We spoke with Wanta to learn more about how JUST works, why he incorporated his social enterprise as a nonprofit, and how he’s used a commitment to learning to grow both the organization and its impact.

JUST Community At A Glance

• Location: Austin, TX

• Founded: 2016

• Employees: 3

• Traction: Loaned over $1 million with a 99.3% repayment rate (average loan size: $1,250)

• Impact: 91% of clients now save consistently, compared to only 19% who did so before joining JUST

• Structure: Nonprofit

• Certifications: Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI)

• Mission statement: “JUST invests in low-income female entrepreneurs to build more resilient communities by providing access to capital and coaching through a network of empowered entrepreneur leaders. Our higher purpose is to create a more just world where people have the opportunity to live with less stress and more joy.”

• Company values: A.C.T. = Action: Learn by doing, do to learn more. Community: Be and do more together. Trust: Begin with a fundamental belief in people.

The Interview

Tell us the story of how JUST got started.

Steve Wanta: I was a business major in college, got out of school in 2000, worked in technology. Every day I would go to work, it was the worst. I was trapped in a land of cubes. I felt stifled in my career and, as the only way out I could envision, I joined the Peace Corps and worked in rural Guatemala. When I finished, I was in the right place at the right time.

This was when John Mackey met Mohammed Yunnus, and they decided to work together as Whole Foods was launching its Whole Planet Foundation. Yunnus said that he could send a team of Grameen Bank staff anywhere in the world as long as there was money. They decided on Guatemala and Costa Rica, and the Whole Planet Foundation sent a team of 10 Bangladeshis who didn’t speak Spanish to Central America. They hired me to go back to Central America and help the Grameen team. It was the best way to learn from the inside out how you do pro-poor microfinance.

Flash forward 10 years with the foundation, and we grew our support of this sort of work to 70 countries and $70 million. I continued to ask why we couldn’t figure out how to do it here in the US in a way that really responded to the needs of the entrepreneurs, a way that was leveraging modern technology. It felt like there was a gap there.

I was fortunate to be connected here in Austin to a venture capitalist who wanted to reimagine his philanthropy by backing entrepreneurs. He and I and another gentlemen, a long-time mentor, sat and talked about how we could collectively reimagine global microfinance for the United States. The venture capitalist, Bill Wood, put up the initial seed money that gave me the confidence to leave Whole Planet and see if we could do something unique and different.

What was it like taking the leap from a foundation job to running a startup?

SW: When I first left Whole Foods, I didn’t know what we were going to do. I didn’t really want to create a lending organization because I know how hard it is. It requires a ton of money, it requires a lot of discipline, and it is an unrelenting job. I had a two-month exit from Whole Planet to make sure I trained my replacement, and it was the greatest time. I had a job, I had all the potential in the world, and none of the responsibility. Day one , it was like, “What did I do?” I actually had to take a nap at 2 p.m. on a Monday. I was like, “Oh, my God. What are we going to do?”

As one does, I got out of bed eventually. And from there, it was this really beautiful experience. I knew we wanted to try and create a system that was about peer support from the ground up. I went to Weight Watchers for a month to see how community came together. At Weight Watchers, they charge people to weigh in every week. It’s a value-add service that they charge people for, whereas in microfinance, I had seen the weekly meetings be perceived as an obligation, not a benefit.

Going through this process of seeking inspiration from other examples in the world, my thinking started to evolve. In April of 2016 we hired our first employee, a woman who was from the community we knew we wanted to serve first: Hispanic women. This woman, Ivonne Salinas, had been a borrower of Mexico’s largest microfinancing institution, Compartamos. It was the first time in 10 years I got to ask a microcredit client what her experience was and she didn’t have a vested interest in telling me what I wanted to hear.

She talked about some of the reasons that it was great, and some of the areas where it fell short. She and I began the process of testing a new concept. What we had to do first was do it the old way. We needed to organize people in small groups. We set a goal of 100 clients. In the course of about a month, we organized 14 small groups and we lent $1,500 to each person, a little over $150,000 total.

We started collecting money; we started building a program. We thought if we could deliver meaningful content in these small groups, they would build stronger businesses. That meant we traveled north, south, east, west, every single week for 14 different meetings. And normally, in a traditional microcredit business, we would be doing that forever. It would be a never-ending series of small meetings that we would have to hire people to staff. And if we wanted to serve more people, we would have to hire more people. The one thing that was abundantly clear for me was that this was very stressful. If we were going to reach our higher purpose, we had to think of something different.

The other two major lessons from that pilot phase were that there was potential, in the community we were serving, for leadership. There were women who clearly demonstrated their ability to be leaders; they were entrepreneurs already. The other aspect we saw clearly was they wanted to give back. They wanted to help their neighbors.

In those three realizations, we saw an opportunity to create something, and that was this eight-week leadership training program, which we developed and launched January 2017. We really didn’t know what we were doing. We thought that if we could figure out how to create great facilitators, there was a chance that they could take this concept to people in their community.

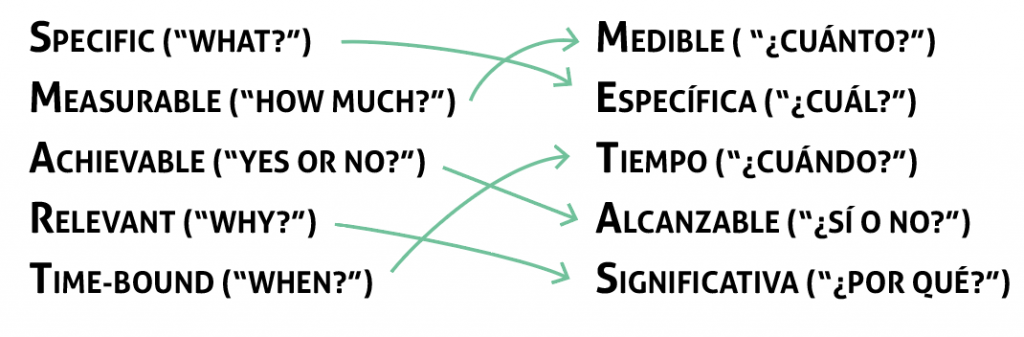

The programmatic backbone of the eight-week leadership training was creating lifelong learners: this idea of test and learn, set goals, and it’s not whether you accomplish your goal or not, it’s whether you’ve learned along the way. That was what we continued to instill. We’ve adapted SMART goals into Spanish. We created eight weeks of games for them to share.

They graduated and, to our surprise, they were excited to invite new people into our program. We started with 25 graduates, and in the course of a month, we had 80 new clients. We were like, “Holy cow. Wow, this might actually work.” Then came the next part of the challenge, which was money.

We’re a lender — we have to have access to capital. As a startup nonprofit lender, not a lot of people are excited to give you money, especially if you don’t have collateral and you’re lending someone $750. We were fortunate to be able to raise some new capital from a family office in Salt Lake City, which allowed us to start another round of leadership training.

That leadership training session in September of 2017 was head and shoulders above the first. We learned so much through that experience. We did a lot of user research on what worked and what didn’t. We introduced far more transparency into the process. The cool thing was we’d been able to build a fully digital from off-the-shelf technology, which has made our operation significantly more efficient and more impactful.

What we believe is, repayment of the loan is a start. If we can help our clients build stronger businesses and build better money habits, we — at a minimum — will be paid back. What we’re seeing now is people saving more money and saying things to us like, “I now know how to save.” And a lot of that is due directly to the community support that has emerged.

How do you understand iteration, failure, prototyping, trying things? How has that been important in your business and with what you teach?

How do you understand iteration, failure, prototyping, trying things? How has that been important in your business and with what you teach?

SW: One of our core values is action. We want to learn by doing, and we want to learn so we can do more. It’s so clear the best teacher is experience. Everything we do, we live first as a team. When we built this leadership program, we went through a dry run every time with our own internal team.

We’re really fortunate to have so much trust in both directions. Our clients trust us and we trust our clients. We have more freedom to stumble. They’ll forgive us. We figure that if our intentions are good and we learn faster and we fix our problem faster, then we’ll get to a better solution more quickly, which means we can do it again and make it better the next time, or add the next product or service.

That has been a really important piece for us to instill in our clients. The idea of Lean Startup hasn’t trickled down to the woman running a cleaning business or the woman selling things at the flea market, and many of our clients fall into that category. We think we can simplify many of those concepts even further. We launched a one-day boot camp for our clients that centers around many of those same principles. It has been eye-opening for many of our clients, this idea of setting a goal and it having specific attributes.

Translating SMART goals to Spanish has essentially been the most important thing we’ve done to instill the idea of testing and learning. We all have dreams, and in order to make those dreams a reality, we have to have goals to give us direction. It’s not whether we accomplish those goals or not, it’s whether we’ve learned along the way. I do believe that our clients are internalizing that concept and are able to share it with their broader community.

Meet METAS: SMART Goals for Spanish Speakers

Leaders have been using the SMART acronym to help set better goals since the concept was first articulated in a 1981 Management Review article, but no one had translated the idea to a meaningful acronym for Spanish speakers until JUST took the time to do so in 2017 (“metas” means “goals” in Spanish).

You said the level of trust you and your clients have in each other has been instrumental to giving you the freedom to stumble. How did you get that?

SW: Give someone money. But in all sincerity, trust is a two-way street. Because we start with money, there is this unique thing that happens. But you can’t just give people money and they’re going to trust you. What we have done and have gotten better at is establishing clear expectations and being consistent in our follow-through, so there is no confusion.

I’ll give you an example. Our first loan is $750. It is by no means enough money for anyone to build the business of their dreams. It’s an instrument of trust. If they are incapable of making timely payments every week for the next 13 weeks, we will not give them a loan increase, though we won’t kick them out as long as their group continues to believe they’re worthy of another chance. But if they fulfill all those commitments and do what they said they were going to do, then we’ll increase their loan amount, right now up to $5,000. We have those same sort of clear, black-and-white policies for our community, and in particular on loan sizes.

So you make it very clear how they can gain your trust, and in being so clear and consistent on that they come to trust you as well?

SW: Yeah. If we can’t fulfill our end of the bargain, we compromise the trust as well.

You mean if you can’t give them what you promised you’d give them?

SW: Yeah. In microfinance, we start with a small number of clients and small-dollar loans. What happens is, you start adding hundreds or thousands of clients and they all start to get larger loans. We have to make sure we can fulfill the capital commitments of the loan demand from our clients. That’s part of our responsibility in this trust game.

Why are you focusing on women?

SW: Women are most excluded from access to capital, access to opportunity. Having women fulfill roles of leadership in all levels of society is really important. There’s research that talks about women reinvesting in their families. And there was already plenty of proof that women in the United States could access capital and pay it back at high rates.

We’ve had some men enter our program, and we are 0 for 3. There were three men who entered JUST and we had problems with all three of them.

What’s your favorite success story of one of your clients?

SW: One woman borrowed $1,500 and started her nail business inside someone else’s nail salon. Her business didn’t immediately take off. So she started to establish more goals. She started to test and learn what worked on social media. Through that, she took a step to move into her own salon with a colleague, also a client of JUST. Through that experience, her business continued to progress. A month ago, she opened her own salon that has 13 chairs — haircutting, manicure, pedicure — and this woman just borrowed $4,000 from us. This is her fourth loan. She was just featured on Univision the other day. Time will tell how she continues to grow her business and make it more established; she’s starting to compete with the formal businesses that we think of when we think of small businesses. She gives JUST, the program and the capital, a lot of credit for what she’s been able to do.

I’ve got another, more human-side story too. One of our clients is a single mom with three kids, and she lives in an affordable-housing community. She buys and sells handbags. Through the JUST program, she looked at her business and saw that she didn’t have control of inventory. It was a classic “I don’t know where the money comes from and I don’t know where it goes. I just know that I end up at the end of the month with no money.”

She challenged herself to save money. She got inspiration from a Facebook ad, and decided she’d save every $5 bill that came across her hands into a separate envelope. Again: single mom, three kids. In one month, she saved $900.

What’s so cool about that story is we’ve had her share it with hundreds of women in our large group meetings. And every so often, in their own small WhatsApp groups, a woman will post a picture and say, “Hey, look at my savings bucket,” and it’ll be this stack of $5 bills.

How did you decide to be a nonprofit lender, and not a for-profit?

SW: It was a very conscious decision. We believe this work needs to have a small and strategic subsidy as part of ruthlessly protecting our mission. As a group that wants to serve low-

income communities and charge them the least amount possible, we need to find ways to reduce our costs. As a nonprofit, we have an opportunity to keep fees low because, for example, we receive services like Quickbooks Online at discounted rates. And the capital we can raise to fund our loan pool appears to be more available. Even if we decide we’ll raise more money or make more money by being a for-profit for other products and services, we can have our nonprofit be the owner of that organization.

Our vision is to be fully financially sustainable. If we do that, we would be one of the first nonprofit lenders in the United States . But we believe that in order to make systemic change, we need to be financially sustainable.

What’s giving you hope?

SW: The women, without a doubt.

Though there’s a Buddhist, Pema Chodron, who says the goal is to abandon hope to lead to fearlessness. To me, that means if we have confidence and trust that our community is capable, we can act more fearlessly. For example, we don’t hope they’ll pay us back. We are confident they will, and we can act accordingly. Instead of focusing on ensuring they pay us back, we can build stuff that helps them transform their lives.

How do you understand iteration, failure, prototyping, trying things? How has that been important in your business and with what you teach?

How do you understand iteration, failure, prototyping, trying things? How has that been important in your business and with what you teach?