In addition to winning the prestigious Buckminster Fuller Challenge, he developed the Living Building Challenge, which is the new pinnacle for sustainable building and design – setting the bar far higher than LEED Platinum certification (for more details about the rigorous requirements of the Living Building Challenge, see our interview with Amanda Sturgeon in Issue 2). Leonardo DiCaprio has handpicked McLennan to design his new restorative eco-resort on a private island off of Belize, which, upon completion, will provide a new model for what is possible in the sustainable design world. McLennan currently serves as the CEO of the International Living Future Institute, an NGO that provides green building solutions and education to raise the bar for true sustainability in the built environment. We spoke to McLennan on Bainbridge Island, Washington, about the genesis of the Living Building Challenge, what it takes to shift the paradigm of an industry, and creating handprints rather than footprints.

What inspired you to get into sustainable building?

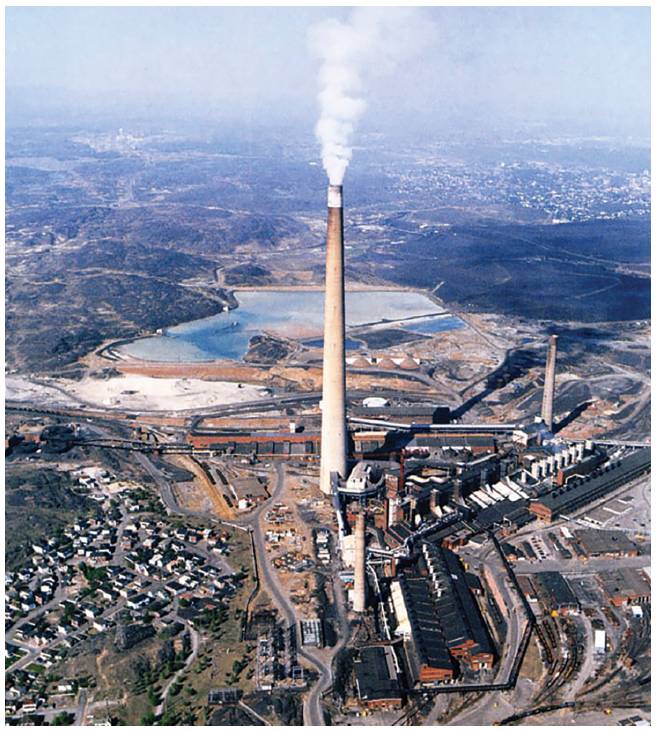

Jason McLennan: I grew up in Northern Ontario, Canada, in a city called Sudbury – a mining town of about 100,000 people. It had over 100 years of mining history. They discovered the richest vein of nickel in the world from a giant meteorite that crashed thousands of years ago, creating the second largest impact crater in the world. It produced a huge amount of nickel and copper, so this town emerged, but to get it, they devastated the landscape. They cut down all the trees for miles around. They had open pit fires to melt the rock, creating incredible air pollution. It basically acidified all the soils, killed off all the lakes, and created a moonscape. They built the world’s tallest smokestack. It’s taller than the Eiffel Tower. You could see it for miles around. It’s like a big cigarette sticking up in the planet, and they built it to stop the local air pollution because it devastated the area so much. They built the smoke stack to send the pollution to the United States, which worked beautifully to kill off the trees in New England. It was the largest point source of acid rain in the world in the ’70s and ’80s.

“The idea of changing the world one building at a time was wearing on me.”

However, in the ’80s, the whole community got involved in a large re-greening campaign to transform the landscape. As I grew up, the trees grew up alongside me. I watched the regeneration of an entire landscape. Sudbury went from being the butt of jokes in Canada to one of the best places to live within the span of one generation. So I became an environmentalist at an early age. We spent a lot of time outside fishing, hiking, and just being in nature. Seeing our ability to completely devastate a place and then bring it back was a powerful lesson because we don’t often get to see the “bring it back” part – especially to that extreme. To participate in that as a child, it made an impression.

In middle school, I started to get interested in architecture and design and I started to get frustrated as I really started to open my eyes to how the city was planned and how development was happening in the community. In any kind of frontier place, there usually isn’t very good investment in infrastructure and buildings and you usually get the worst of it because the powers-that-be live somewhere else. So there was crappy architecture and crappy buildings for the most part. There definitely wasn’t green architecture happening there.

Also during middle school, there was a boom in nickel prices, and they were building a lot of new developments. A developer ended up buying this area where I had planted trees as a kid at school and the first thing they did was cut down all the trees that we had planted when we were younger, which was like a knife in the heart. They scraped away all of the soil that we had helped heal and made a flat parking lot and a strip mall. It really angered me because it was just so careless.

I started to wonder why we built buildings that were so lifeless and don’t take into consideration what is unique about a place. That got me thinking, and I knew I was going to be an architect by 10th grade. The “green” side of it, for me, was just the way we had to go. I had a calling pretty early on that this was what I was going to do. I started taking drafting classes and art classes and everything I could to get ready to be a designer.

McLennan led the design on Heron Hall Living Building project

“People don’t seem to have either the honesty or the courage to figure out where they really want to get. You can imagine your truly ideal life or job – but why don’t you actually try to get it?”

Tell us about the genesis of the Living Building Challenge.

JM: After I graduated from the University of Oregon, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do exactly and I ended up getting a call from Bob Berkebile, who is one of the pioneers in green building. Bob was looking for somebody who understood sustainability at a deep level and he hired me right over the phone.

We had this project in Bozeman, Montana that was funded by NIST . The premise was to design a truly sustainable building, but nobody knew what a truly sustainable building really was and it became my job to figure it out. I came up with this term “living buildings.” We started coming up with the rules for what a living building would be in 1997. In 1998, I published a paper on living buildings before LEED was around.

This building in Montana was going to be everything that the Living Building Challenge describes, but it was killed for political reasons and never happened. I had worked three or four years full-time on this and then it went away, which was really unfortunate. The project ended and I said, “Well, what the hell do I do now with this knowledge?” We had had millions of dollars to spend on research – architecture firms never get that much money to do research and I was in charge of all the technologies and all the systems to figure out what true sustainability would mean. We felt like we had to get this information out, so I started a green consulting group called Elements where we started training other architects. We worked with our competitors, which was a new thing. Why would you teach HOK how to do what you know? Well, that’s how we make change. You learn more as a teacher than as a student.

Because of this, I ended up becoming a partner at the firm. I started out as Bob’s intern and within a few years, I was a full partner in one of the most important firms in the United States. I was the youngest partner at the firm, doing projects all over the place on sustainability and I had made it as an architect. It was an honor to be selected. But you make it and then you go, “Is this it?” It wasn’t my goal to be a typical architect.

At that point, LEED had emerged and was doing a lot of great things, but it only went so far. I had this sense of, “Here is where we need to get to and LEED only gets us to here and there’s a huge gap between the two.” There was no sign that the industry was in any way focused on going beyond LEED – it was just stuck in this paradigm that had been created. That’s the way it works though, right? People get locked into a particular perspective. LEED started in 1999 and by 2004 it was really exploding because there was a need in the market for some definition. Better designers were making buildings work better. The financial barriers were coming down. It was good, but there was complacency setting in and it became, for a lot of firms, about chasing points . Their eye wasn’t on the ball, and they were focused on the wrong things.

I had started thinking that we needed to shake this up and then, parallel with that, there were real world events that I started seeing. Katrina happened in 2005. Al Gore’s movie “An Inconvenient Truth” came out. You started to get a sense that, not only were we not moving anywhere fast, but we actually had a real timeline. There was actually a huge urgency to make changes, but we were acting as if there weren’t.

I kept working on this idea and published my book “Philosophy of Sustainable Design” in 2004 where I talked about “living buildings” to start to change the conversation. I was definitely getting anxious for change to happen, and one night, I came home late and realized that the idea of changing the world one building at a time was wearing on me. You work on these projects with these two- to five-year timelines and you hope that they have the impact that the Bullitt Center is going to have, but you don’t always know because shit happens. I just began to get very anxious about the future, so I came home that night and said, “I’ve got to change.” Even though I was a partner and everything was great, I knew I had to make a change. On a whim, I turned on the computer and looked for green jobs out there that might be interesting. Almost the first thing that came up was that the Cascadia Green Building Council was looking for an Executive Director, and I thought, “Oh, that’s interesting.” I kind of knew that it was the right thing to do, which was really scary, but I knew that I couldn’t launch something like the Living Building Challenge from a for-profit architecture firm. It would’ve just seemed like a marketing thing or like it was a way for us to get work. It needed to rise above that to the public realm.

Cascadia was the rebel wing of the US Green Building Council (USGBC). Its reputation was that it was where the troublemakers of the green building scene were in the greatest numbers, and I kind of liked that. They didn’t know when I interviewed that I had the Living Building Challenge. It was a secret, but when I came to my first board meeting, I said, “Well, thanks for hiring me, but I have a surprise for you. I have some intellectual property that I want to give to your organization for free, but there’s a catch and the catch is, we have to agree as a board to put everything we have into doing this work and if you don’t, I’ll give it to someone else.” To their credit, they voted unanimously to do it and suddenly we were going to be putting out a different standard than LEED, as a USGBC chapter. That was 2006.

We had a lot of battles at the beginning. Everything I pushed forward was illegal everywhere in North America. So that was one hurdle . Everything I asked for in the materials world was not available. That was another hurdle. Solar was prohibitively expensive. But I knew it was achievable because we had done every aspect of the challenge in pieces at BNIM . People said, “You can’t do it.” I said, “No, I’ve done each of these things, just not all together.”

In Joseph Campbell’s “The Power of Myth,” he talks about following your bliss and putting yourself in the field of bliss of others so that people will then help you. There’s a bit of a spiritual dimension to that, but I just knew that this was the right idea at the right time. Intellectually, you doubt and you wonder, but at my core, I knew this was going to happen. It has unfolded as I felt it would, which has been cool.

The Bullitt Center designed by Miller Hull follows McLennan’s Living Building Challenge Standard. Photo: Nic Lehoux

“Change is not going to work if you have to be a green saint. You have to change the paradigms fast and in such a way that it’s easier and it’s better.”

In terms of shifting the paradigm, it seems as though the formula you’ve devised is setting a standard that is so high that it’s borderline audacious. Is that what it takes to shift an industry or paradigm?

JM: That’s part of it – the big hairy, audacious goal theory – but that’s only part of it. It’s not so much about an audacious goal; it’s about putting our efforts towards the actual ideal outcome that we want. Most people start by compromising immediately on what they want because they have a hard time imagining going from where they are to where they need to go. As a result, they begin to compromise and then get down the road three years later and they really wanted to be in an entirely different place.

It’s like when a ship sails and it has to keep tacking with the wind. To the person on shore, it looks like the ship is heading in the right direction, but if it’s a few degrees off, it will end up miles and miles from the actual destination. You always have to know what the destination is, and that’s something that the whole green building movement – and most movements for that matter – don’t get. They don’t take the time to clearly articulate the vision of success and hold that sacred and refuse to compromise. When you do that, that’s when the magic happens. So it’s not so much that it’s an audacious goal, because you can set an audacious goal that still isn’t your ideal. You can spend your whole life and energy wondering why you never quite fulfilled or reached what you wanted to. It’s all about having that vision.

People don’t seem to have either the honesty or the courage to figure out where they really want to get. You can imagine your truly ideal life or job – but why don’t you actually try to get it? That is the question. Why do you try to do something else for four years and then maybe later you’ll do what you want? The odds are, you’ll never get to that ideal job and you’ll have spent all those years of your life doing something you didn’t want to do. People don’t feel like they have permission to go to that next realm.

With green building, as long as LEED Platinum was the paradigm, everyone tacked to that. But if the real goal is way over there, then why are we spending 20 years re-jiggering the economy toward something that is still going to lead to a failed ecological state? If you have all the time in the world, baby steps are fine. But if you have a limited amount of time, you may have to step much bigger than a baby step. You actually have to think about how long you have to get to the ideal place. That’s why all these false promises by politicians – x percent reductions by 2050 or 2030 – are all bullshit. It’s all outside of their jurisdictions. It’s never enough to get to where we actually need to be so it’s completely useless. What would we have to do if we actually believed in the science? What would we have to do in 10 years, not in 50? It means we’d have to start building living buildings. We’d have to start dumping the fossil fuels out of our economy now and as fast as we can.

How do you get an industry that sees LEED Platinum as the pinnacle to “re-tack” the boat and focus on living buildings as the new goal?

JM: Our strategy has been to use inspiration instead of guilt, which is why it was really hard until we had the first living buildings completed. It’s one thing to talk about these things, but when you can show people the Bullitt Center, they can say, “Well, it works in Seattle.” I can then say, “Do you want to see one in Pittsburgh?” They start to run out of excuses and it changes the entire model. It really works toward that saying, “The best way to make changes is to make what you want to change obsolete.”

Tesla is making the internal combustion engine obsolete. Living buildings are going to make regular buildings obsolete – that’s my goal. Once you reach economic parity and you have a better product, it’s almost an instantaneous change. We fight and fight and fight and all of a sudden, you have this huge shift. Think about laptops or cell phones. Anything society adopts goes through a denial and resistance phase, then you have early adopters, and this curve where the better thing is more difficult because the paradigm we’re in is not set up to support it. Everything is set up to support the current system.

That’s why doing the right thing is harder than doing the wrong thing. Change is not going to work if you have to be a green saint. You have to change the paradigms fast and in such a way that it’s easier and it’s better. When you do that, then you win. That’s where we’re getting with solar soon. That’s where we’re getting with the internal combustion engine. Imagine in 20 years if they stop making internal combustion engines in vehicles altogether – nothing new out of the assembly line ever again with an internal combustion engine. It’s possible. Now what would that change for air pollution? What would that change for war? Same with coal plants and all the damage there. We could be there within that timeframe because the costs are coming down. It’s getting more elegant. That’s what we’re trying to do with buildings as well.

For someone who can’t afford to design something from scratch or who is living off a small income, what does living sustainably look like, in your opinion?

JM: You do what you can, first of all, and you do what you can afford to do. Not everyone can afford solar panels, but you do what you can. We have to change the system so that it’s achievable for everyone as opposed to expecting everyone to be able to afford the right thing in the system that’s not set up for it. I tell people not to feel guilt and shame if they can’t live in the perfect eco-thing yet. If they can’t afford it, that’s not their fault.

But there is a lot that people can do and those are the things that they should do. People can lower their footprint in a lot of ways. Hopefully, we’re also talking now about “handprints.” People can influence their handprints as well, which are the positive actions. This is another paradigm change – why do we always only count the bad? We try to minimize our footprint, but you’ll always have a footprint. You don’t have to have money to talk to somebody else. Influence them, and when you help them reduce their footprint, that’s your handprint. When you teach your child about something or you volunteer for a charity, you’re increasing your handprint. You can create a rich world. It’s not always about what you buy and what you don’t buy to reduce your footprint. Your handprint can be much more beautiful. It’s just a different paradigm.

You guys have a footprint. You cut down trees and you use inks . But by having people understand these stories, you guys are handprinters, right? You basically believe you can do more good in the world by causing the impact that you have. In the end, you’ll always have a footprint and can make it as small as you can, but what we really should focus on are the positive things that we can do, which is what you’re doing. You’re telling the stories of what needs to be told and getting information out to change people and that’s much bigger and has a much more positive impact than the FSC paper .

Where would you like to see sustainable design go in the next 15 or 20 years?

JM: I’d love to say that all buildings will become living buildings, but everything we’re talking about is just the new paradigm. I don’t know if it’s 15 years or 30 years, but the Living Building Challenge will either provide the roadmap to make the change or it will be the safety net when we have to change. If we don’t change in time and we’re truly fucked, we’ll have to make radical changes and, hopefully, having a few decades of models like the Bullitt Center that show us that we have a better option will help. Plan A though is that we change in time to make a difference. Either way, we have to act like we have to do it now, as fast as we can.

How do the challenges that you are experiencing today differ from the challenges in 2006 when you first started launching this?

JM: People don’t think I’m crazy as much as they used to. We have proof. It’s not just theory and ideas. It is still just in some markets in some places, but more and more people are saying, how do we get there faster now? Why aren’t we doing it? Now, it’s taken on a different life where when you see another developer pull it off, you want to do it, too.

We are trying to question it too – for example, what are we doing to continue to scale the rapidity of the change itself? We’ve changed state laws in a few places, which we’ve done for water . We’ve tried to remove the barriers and provide models. It’s all helping, but in the end, there’s going to be some sort of societal force that will create that tipping event. Economics will also play a big part of it and disruption will play a part of it.

An overview of Blackadore Caye Restorative Island, the restorative eco-resort McLennan is partnering with Leonardo DiCaprio on.

Of all the projects you’re working on right now, what is the most exciting one for you?

JM: Probably what I’m doing in Belize, and my house, for different reasons. With the house, suddenly I have to follow all my own rules now. What a pain in the ass ! I set up all these firewalls so that I can’t influence the committees and the auditors and my board members. So, it’s very difficult !

What can you tell us about the Belize eco-resort project with Leonardo DiCaprio?

JM: It’s an opportunity to go further and at a larger scale than anyone’s done with solar and renewables, with habitat restoration. For me, it’s an opportunity to influence a demographic that needs to be influenced almost more than anyone – the people who have the most influence in how the world is run and need to get this. The average citizen’s footprint or handprint is only so big. If you can influence heads of state, prime ministers, presidents, CEOs of the most powerful corporations of the world, and celebrities who have thousands of Twitter followers, you can change their paradigm and they start to ripple out change in their networks and their universes. That’s the scale issue.

For me, this project is all about getting the longest stick you can and trying to pry something open. It’s very easy to be cynical about something like this project if you just look at it on the surface and say, “It’s a playground for the rich,” which it is. But I have playgrounds and they have playgrounds, but they’re different. With this project, we’re able to afford to do things that, right now, are not yet easy to afford. Those who have resources should pay for those things first to make it cheaper for everybody else, to make it easier, to be the guinea pigs. It should be those who have the means to do it, not the poor. We shouldn’t experiment on the poor. We should experiment on the rich. Let them drive down the costs of things.

We can get someone like this to start changing everything just by visiting a place that’s better than anything they’ve ever experienced. There’s no fossil fuels anywhere, there’s no plastic or petro-chemical products anywhere, the water is all from the sky, the energy is from the sun and the experience is better. They will be like, “Why are we not doing this in my corporation, my manufacturing facility? Why are these not the ordinances in my nation? Why am I not doing this?” We can show them it’s not weird, and in fact, it’s better. We can start to change some of these people. These are the people who have the ability to change the world and they have a mouthpiece to the world. When I have celebrities using composting toilets and hopefully loving it, then maybe I’ve been successful in making this whole shift. So that’s my reason for working on this project and the project is, we hope, going to be a game-changer. It’s going to get a lot of attention. It’s already getting a lot of attention.

What is inspiring you or giving you hope for the future?

JM: I’m really excited about solar right now – the economics of it has changed so rapidly in such a short time, even faster than a lot of us predicted. We’re getting close to grid parity with fossil fuels now and it’s already there in a lot of markets. Imagine if we could dump fossil fuels within the decade! It would literally change the world. I’m pretty excited that I can see the light there. I hope we get there soon.

What advice do you have for younger generations?

JM: Give a shit.